In the Milan exhibition ‘Miranda July: New Society’ at Fondazione Prada, there is a short blond wig hung up on the wall, which July bought when she was a struggling artist working as a stripper for extra money in her twenties. There’s no mention of it, but it is displayed as one of the costumes from her performance Love Diamond. However, that object’s journey from a peep show in 1990s Portland, Oregon, to a major solo exhibition in Milan feels like a fitting microcosm of the show.

That’s not just because ‘New Society’ charts 30 years of July’s career, from her early days in the West Coast punk scene and ending with her latest works, made as an acclaimed artist whose work spans performances, videos, installations, major motion pictures and novels. But also because July’s work has always explored the unpredictable, strange, joyous and heartbreaking turns life can take.

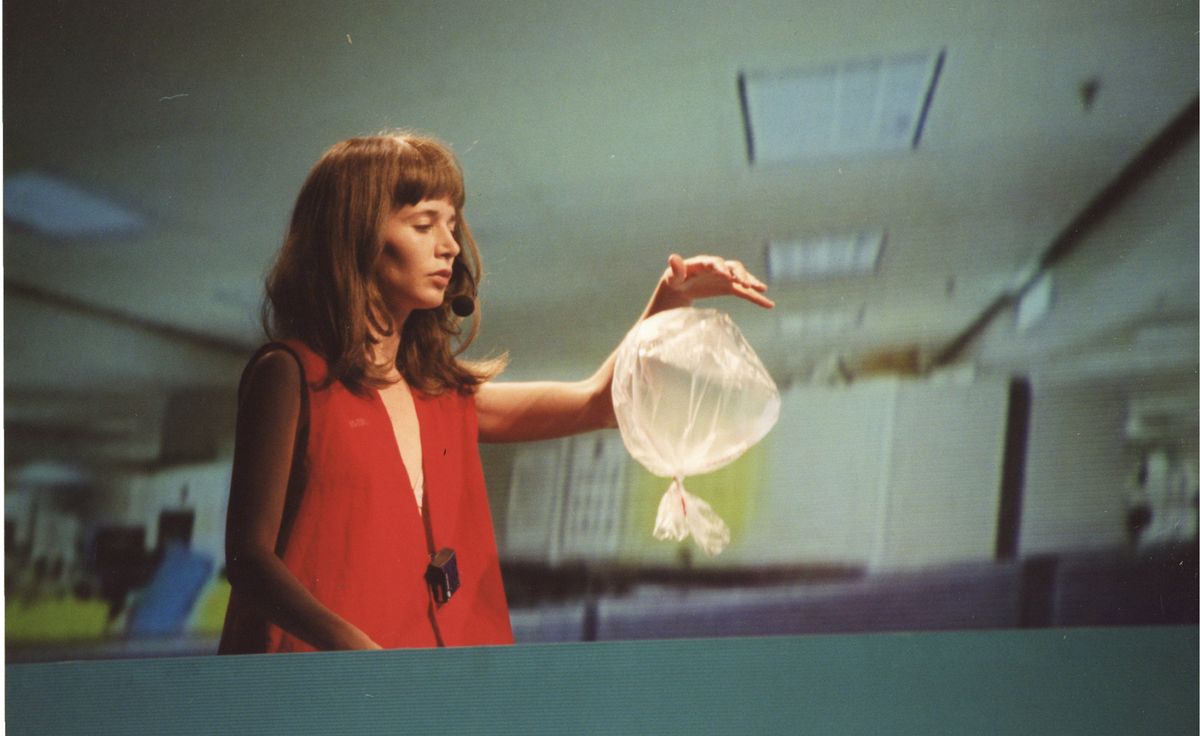

Miranda July in Love Diamond, 1998

(Image credit: . Portland Institute of Contemporary Art, Portland, Oregon Courtesy Miranda July Studio)

In July’s world, a ride in an Uber one day evolves into I’m the President, Baby, a performance created by the artist and her one-time Uber driver, Oumarou Idrissa, that brings viewers into Idrissa’s home. There’s also the call from a random telemarketer in The Philippines that became Services, a collection of photographs made by July and telemarketer Jay Benedicto. A trip to the theatre, meanwhile, turns into an attempt, between artist and audience, to create a new society from scratch in the 2015 performance from which the Fondazione Prada show takes its name.

All these works and more are on display in the new exhibition. Together, they create an entertaining and moving exploration of our insatiable desire to connect with something outside ourselves, and just how bad we are at doing it.

Following the show’s opening, we sat down with July to discuss how it felt to revisit her earlier works, a new piece, F.A.M.I.L.Y (Falling Apart Meanwhile I Love You), made specifically for the show, and more.

Miranda July interview

Miranda July, @craigmontyjames (C.M. James), and @thongria (Zoë Ligon) in F.A.M.I.L.Y. Ceiling, 2024 Still from video

(Image credit: . Portland Institute of Contemporary Art, Portland, Oregon Courtesy Miranda July Studio)

Wallpaper*: The new show is such an extensive archive of your work. There’s a poster from your first exhibition, made when you were 15, clothes from your early video performances and so much more. What compelled you to archive everything from such a young age?

Miranda July: It’s sort of two things. Initially, it was that my dad kept an archive and so as a little girl I just thought that’s what people do and I just kept everything.

Then around the time I made Love Diamond, my first performance, I stayed in New York at the NYU housing of someone who worked in The Fales archive, which is a very famous library archive. That’s when I realised that what’s saved is what’s remembered, and what’s remembered becomes history, and history shapes reality, our sense of what this Earth is.

I knew no one was going to ask some young punk performer to save things, but I had been doing that and knew that I should just keep doing it. Not to any particular end, other than that everyone should probably be keeping an archive so that we have records of what different kinds of lives were like.

I actually didn’t think of including that stuff in the show until pretty late. It wasn’t part of the original idea for the show. Mia [Locks, the curator] had signed on and we were talking about the different performances and at some point I said, ‘I have this whole room with everything from all of those performances.’ Then the show really shifted.

W*: How did it feel to go back into those boxes and return to all these things you probably haven’t looked at in a while?

MJ: You know how when you’re going through old things, old pictures or letters, and it’s like you’re stuck in molasses or something? You start reading and you just lose time. But we were on a tight schedule, so I couldn’t do that. So I’d be trying to hand Mia relevant things as I went through the boxes. She just sat there while I kind of spun down into a letter to an early date of mine or something. But then there was also every receipt I ever got, every FedEx bill… so yeah, there’s a lot of stuff that’s not in the show.

Miranda July, Audience participants in New Society, 2015

(Image credit: Courtesy of the artist)

W*: Did you feel like you learned something about yourself or your practice through that exercise?

MJ: I guess you always feel like you’re not trying hard enough, or like, ‘I’ve really got to get it together, or make this thing better.’ You have these feelings and then you realise you’ve been trying at that most extreme level for a really long time now.

The first time I walked through the show was right before the opening and I just walked through it rather quickly. When I got to the second floor to look at F.A.M.I.L.Y, I felt some relief. I felt like, ‘Well, this is a good direction for this person to have gone in. It seemed like it was a little bit more of an easier life [by the end than it was at the beginning]. I mean, granted, that person was also writing a novel that was really hard, but I like the progression of the show. It just generally feels good. I guess also that I’m not still 24. That’s just a relief.

W*: You say ‘that person’; do you feel like you’re looking back at someone else when you view your previous works?

MJ: Weirdly, I still have a lot of those [performances] memorised and the movements still feel very familiar. In Love Diamond, my choice to wear a swimsuit means that now, at twice the age I was then, I get to look fascinatedly at my former self, almost the way I look now at my [own] child’s body with such awe.

I can look at my younger self and see there’s just a sweetness; my face is so much rounder. And yet, it’s all just me. And I remember how it felt to perform that, and I also feel giddy because I know I’m going to perform again.

W*: Speaking of the swimsuit, I noticed at the opening how many people stopped and looked at the clothes from your performances, which are displayed along the wall. I know you often dress up in your studio when you’re writing, and it seems that clothing feeds into your storytelling.

MJ: I remember thinking this bathing suit had an amazing pattern. So, it was like a piece of art to me, and getting to wear it was part of the piece. I knew that it was a wonderful thing to get to look at, even apart from my body, as you say.

I haven’t really said this, but that first wig, that’s now on the wall, I had because I was also a stripper. I worked at a peep show. And so, it was the same wig as ‘Penny’ who was in the peep show. So, I look at that wig and I’m a little like, ‘Oh god, I literally made my money in that way.’ I remember being that age and thinking, ‘Well, I can use it for this performance too’, because my hair was always punk and I wasn’t going to make any money [with it].

Then I remember I felt very proud when I bought a longer wig specifically for a show. It felt really professional to me that it wasn’t my old stripper wig.

Miranda July, Ripped Poster, 2017

(Image credit: Published by Printed Matter, New York Courtesy of Miranda July Studio)

W*: ‘New Society’ is the name of the performance you’ve done but why did you choose that work for the name of the exhibition?

MJ: I have to admit that the Prada Foundation suggested it early on. Which is so unlike me, I can’t think of any other time when I’ve taken a suggestion. But we both thought it was perfect because both words are as broad as they can be, and yet they create a feeling. It’s so hopeful, but sad. [Maybe we need a] new society, or maybe the new society exists in each person, or maybe it is an idea that you hold in you.

I can apply each piece in the show to that idea. It works as a touchstone, how it holds against all odds, holds this candle of hope, or curiosity, alongside a desperate feeling.

W*: Would you say that’s the connection between all of the pieces in the show?

MJ: That and also certainly a different way of handling power. The giddiness and the excitement of having power and handing back and forth; and handing the vulnerability back and forth too.

My girlfriend just watched New Society and she [said], ‘So was any of that ad-libbed? Or was it all memorised?’ And [said], ‘Oh, it’s all memorised.’ Obviously the looseness is there. It could go out of control at any moment, from any person in the audience, or by the audience together. But nonetheless, every little moment is memorised, because that has to be true for the looseness to also be held.

W*: That tension between the controlled and the uncontrollable is one of the most exciting elements of the performances. I remember there was a point in New Society when you asked the audience if anyone played piano. And I thought, ‘What if no one played the piano? What would she do?’ Do you have a back-up plan for things like that? Or is that risk part of the piece?

MJ: I had to write it by rehearsing that every week with an audience, and adjusting it according to what happened. So, it’s almost like making an app or some piece of technology where the user experience has to be developed. In fact, I had just made the app Somebody with Miu Miu, so it really did inform that process because it was iterative. You can make a version and then remake and remake it.

The fact that I never did it in theatres that held more than 200 people meant that I always knew that the tickets would sell quickly, and that the people that would buy them would be my biggest fans. I also knew that because they were my fans, a certain percentage of them probably played piano.

‘Mask’ from Services by Miranda July with Jay Benedicto, 2020

(Image credit: Commissioned by Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazin, Edition 46, Munich)

W*: I imagine that element of risk drives the work in some way though?

MJ: One thing I have just realised is I’m so happy in my internal world, my fantasy world, which is also my writing world, that for me to do something in the ‘real world’ I need really high stakes. Otherwise, I’m not interested. So, I think that’s part of it. I need to be a little scared or I’ll just stay in and think, which is so fun.

W*: Your newest piece in the show, F.A.M.I.L.Y, seems to straddle your fantasy and performative worlds. It’s situated in your personal world – in your studio where you write – but you have these almost ghost-like figures come in and perform alongside you.

MJ: Every other piece in the show had its audience, whereas F.A.M.I.L.Y hasn’t yet. So I’m nervous about it and still working on it. I knew that this show would be between the time of me finishing my new novel and it coming out, and I think I have learned, barely, to try and make a process that’s appropriate for the time and for who you are going to be in that moment.

I knew that [the work I made for this show] needed to be something pleasurable, I needed to enjoy it. I’m willing to go through hell for a lot of these things, but that’s not always a given. For this one, I just kept putting away ideas, taking turns towards things I could do myself and enjoy doing. I bought the biggest iPad you can get because I get to edit it with my fingers moving everything. So, it’s quite sculptural putting everything together, using this app that is made for a baby to use. It’s not hard, but I’m really pushing it.

W*: In the booklet that accompanies the show you say, ‘I often thought of yearning as one of my materials. Every new technology promises a new kind of intimacy that might somehow break through, make us feel not alone.’ I never really thought of technology that way.

MJ: Part of it is that after a while you realise that these technologies come and go. Facebook still exists but we don’t use it as much. And now with Instagram, I was thinking, what specifically do we want from it? Why exactly is the visual part so important? And I realised, ‘Oh, it’s because we want to be looked at lovingly, so that we feel OK.’ But, of course, Instagram [as a business] has to do the opposite of that. In order to be a successful business, it had to just create more need for that rather than saving it.

So one idea behind F.A.M.I.L.Y, was that I’m just going to do that. I’m just going to consummate this. And then I’ll come up with this new kind of sex and a new way to consummate it, because it’s going to be mediated through technology, but we are going to love each other, have each other, somehow merge, somehow look at each other that lovingly.

I mean it’s very clunky, and I left all the artefacts [of that effort] to kind of keep the humour of that, because that’s not really possible, but I think that’s partly why so many times people merge, or mirror, or go into each other. It’s like we’re each other’s newborn babies or something. So, it’s sexual, but very innocent.

Miranda July, ‘New Society’ runs until 14 October 2024 at Fondazione Prada, Milan

fondazioneprada.org

Exhibition view of“Miranda July: NewSociety” Osservatorio Fondazione Prada, Milan. Photo: Valentina SommarivaCourtesy: Fondazione Prada. Miranda JulyF.A.M.I.L.Y.(Falling Apart Meanwhile I Love You), 2024

(Image credit: Courtesy of the artist)