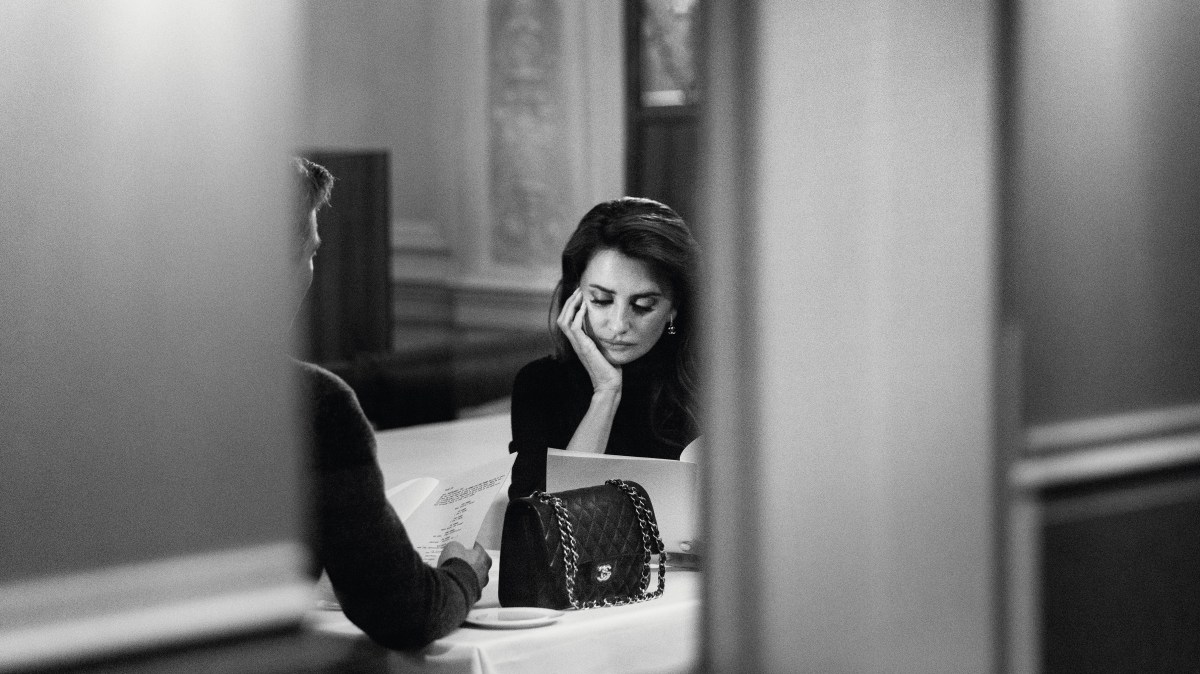

There’s not much that could hold its own on screen with Penélope Cruz and Brad Pitt. Somehow, in a new advertisement from the house of Chanel, the brand’s 11.12 handbag just about manages it, perched on a dinner table between the pair as they smoulder away in black and white, discussing how they would like their steak cooked. There’s barely enough time for the viewer to form the thought “get a room” before they do precisely that.

This article contains affiliate links that can earn us revenue

The Chanel ad features the brand’s 11.12 handbag

INEZ AND VINOODH

It’s a ménage à trois that has precedent, a retooling of a scene from Claude Lelouch’s 1966 New Wave classic Un homme et une femme, in which two widowed individuals meet and fall in love or, at the very least, lust. Cruz takes the role immortalised by Anouk Aimée, while Pitt’s part was first played by Jean-Louis Trintignant. As for the bag, the original was Aimée’s own, placed in front of the camera on a whim by Lelouch. One must assume that the iteration in this remake by Inez and Vinoodh, two of the fashion industry’s favourite photographers who also happen to be married, is box fresh.

Jean-Louis Trintignant and Anouk Aimée in A Man and a Woman

CLAUDE LELOUCH

It might seem hyperbolic to endow a handbag with main character energy. In the context of modern luxury, however, it isn’t. Chanel is just one of the brands whose profitability is built on arm candy, along with certain other key brand signifiers such as perfume.

Why? Because the luxury handbag is a means for the modern woman to cement her identity; to signal her status when she is out in the world. “Iconic” is an overused and often entirely misemployed word. Yet there’s something remarkably like religious fervour that gathers around certain bags today, Chanel’s among them.

Gabrielle Chanel in 1957

MIKE DE DULMEN

No surprise that it was that ultimate modern woman, Gabrielle Chanel, who gave the world the handbag as we know it now (not to mention the first perfume linked to a fashion brand). She launched her first one in 1929, designed — the clue is in the name — to be carried by hand. The real breakthrough came with a later reconfiguration, the 2.55, launched in February 1955, which had shoulder straps inspired by those found on army bags. And lo and behold, the hands-free revolution came about and with it a new way for women to burnish their own brand, not to mention for actual brands to make money out of them doing so. Oh yes, and to carry stuff around with them too, of course.

Jane Fonda, carrying a Chanel bag, with her husband Roger Vadim, 1965

GETTY IMAGES

The rise of the handbag over subsequent decades as a commercial proposition for brands and a nigh-on existential one for many consumers, is intimately related to the rise of women in the workplace. The 11.12, which has a clasp that features the brand’s double-C logo, was Karl Lagerfeld’s 1983 tweak of the 1955 original. The starting price for this particular beauty is £8,530 (chanel.com), a price tag that is evidence in and of itself of the financial power of the kind of woman for whom such a bag was first conceived and who has carried it in ever-greater numbers since.

Chanel autumn/winter 2024

You are never going to have to worry about a classic Chanel number going out of fashion, as evidenced by the fact that Aimée’s and Cruz’s, despite the 58 years that lie between them, are so similar. Nor do you have to fret about growing out of it in other ways: growing too old for it, or too — forgive me, but this is in the back of many people’s minds when they spend serious money on fashion — fat for it.

The brands can relax too. They aren’t going to be left with outmoded stock on their hands. They don’t have to stress about the complexities of clothing sizes. Producing clothes is a far more tricky business model than producing bags.

It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to label ours the Age of the Handbag, nor to declare this Gabrielle Chanel’s most enduring legacy.